Gendered Ethnographies: Horace Kephart and Emma Bell Miles

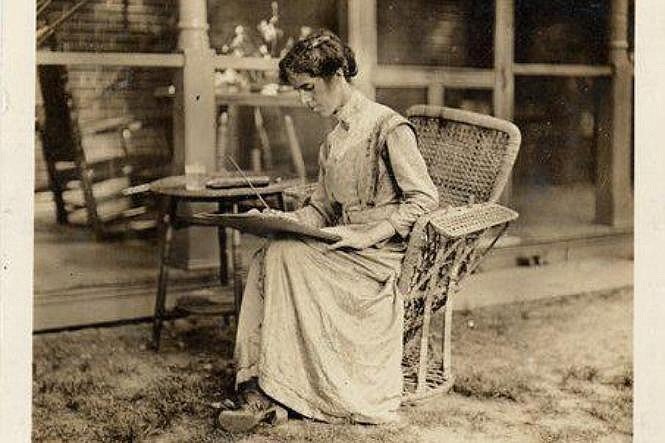

Emma Bell Miles watercoloring at her home on Walden Ridge near Chattanooga. Courtesy Chattanooga Times Free Press.

Sheila Myers

By Sheila Myers

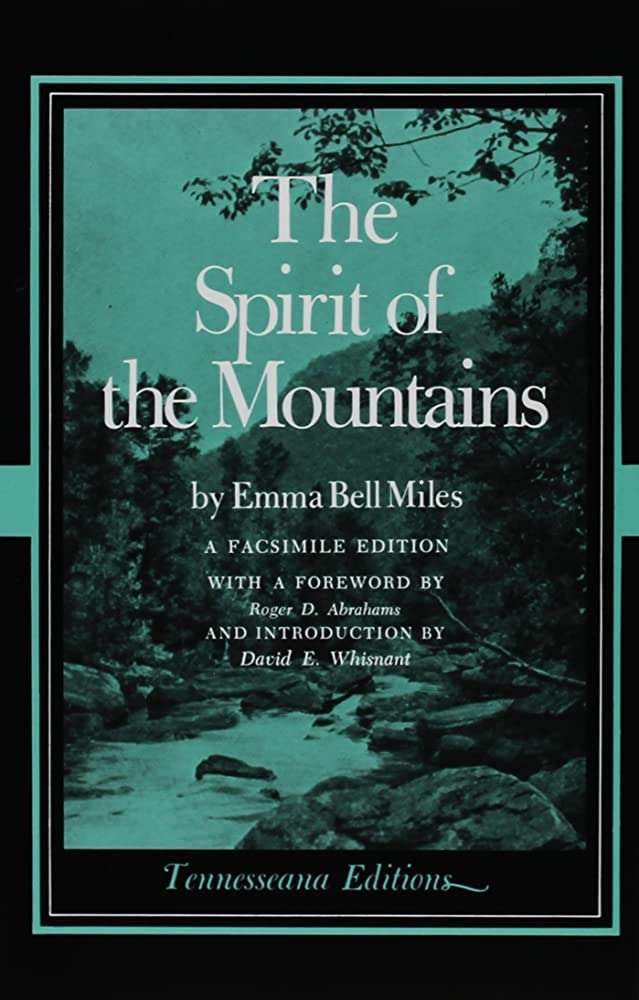

Anyone researching the Appalachian culture at the turn of the 20th century is likely to find the ethnographies of Emma Bell Miles and Horace Kephart. Miles’ The Spirit of the Mountains (1905) and Kephart’s Our Southern Highlanders (1913 and 1922) document the daily lives of the people living in the mountains of the southeast United States in the early 1900s. Their lyrical prose on the familial culture, unique dialect, art and music—influenced by isolation—are entertaining and insightful reads.

An examination of these two authors reveals parallels in their writing style and the influence their education had on their perception of the culture. Miles went to college for two years at the St. Louis School of Art. Kephart attended college in the mid-west and then went on to graduate school at Cornell University in 1881 to study history and political science. Both authors had educations that were for the most part beyond that of the people they were studying. Rather than condescending, the authors had a penchant for describing their neighbors with grudging respect and awe for their resiliency. Moreover, both authors were amateur naturalists. Kephart wrote numerous articles for magazines such as Field and Stream on camping and the flora and fauna of the region, while Miles wrote and illustrated a book titled Our Southern Birds, in 1919. Both weave vivid narratives of the natural beauty of the region throughout the Spirit of the Mountains and Our Southern Highlanders.

Furthermore, Miles’ and Kephart’s ethnographies were written during a critical juncture in Appalachian history. Within a few decades of their book publications, Appalachian culture was rapidly transforming. The economy was changing from a bartering to a monetary system. New technology allowed railroads to snake their way along the steep ravines and ridges of the southern highlands to access and exploit minerals and timber. Tourists from the cities were flocking to the region to build vacation homes or stay at hotels that were springing up in the towns and villages. This created mounting public and private pressure on native residents to move or lease their land for lumber and mining rights, or government preservation.

However, that is where their similarities end. Horace Kephart and Emma Miles were a paradox. Gender bias placed constraints on Miles’ ability to pursue her artistic passions while providing Kephart an advantage. Gender also appears to have played a role in what each author chose to highlight in their works, perhaps because they had different opinions of the importance or what might ‘sell’ to the average reader (mostly from the northeastern cities). Although one would expect gender to factor into how and what these two authors chose to write about, gender also played a significant role in their artistic freedom. Family duties hampered Miles’s ability to conduct artistic work. Kephart, on the other hand, abandoned his wife and six children to live in self-imposed solitude. This gave him much greater freedom to pursue a professional life that was denied to Miles. In addition, Kephart was an outsider looking in on the culture he adopted, while Miles was an insider looking out and with conflicting emotions, at what could have been her life had she chosen a different path than to remain in Appalachia. Finally, because her life was cut short at age 40, (unlike Horace Kephart, who died at the age of 69) Emma Miles never published her in-progress manuscripts. Nor did she achieve the accolades given to Horace Kephart, who has a mountain peak named after him.

George Ellison and Janet McCue recently published a thorough biography of Kephart titled Back of Beyond (2019).[i] He was born in Pennsylvania in 1862 and raised in Iowa. After graduating with a Master’s degree from Cornell University and a research stint in Italy, he married Laura Mack at age 25. He took a prestigious post as the Director of the Mercantile Library in St. Louis, Missouri. At the time, the library was a center of social activity and scholarship, and Kephart, who was an introvert, found himself thrust into the spotlight. By all accounts, he was a studious and steadfast employee, but he may have found the attention disconcerting and at times overworked himself. He found release through camping, hunting, and alcohol. Time spent away from his job to follow his adventurous spirit, and a struggle with alcoholism put a strain on his marriage. Laura left him and St. Louis to move back to her hometown, Ithaca, New York with their six children.

Due to his extended absences from work, Horace lost his job in 1903 and suffered a nervous breakdown. Because of his stature in St. Louis, his downfall was a public event—making the headlines in the St. Louis newspapers. He found his way to the Appalachian Mountains to heal; eventually ending up in Bryson City, North Carolina on the border of what is now the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. He began experimenting in outdoor writing. In 1906, he started writing his first book, Camping and Woodcraft, which was eventually published in 1917. Very little is known about how his family managed during the time he lived in the mountains. A family letter written by his daughter indicates his wife Laura may have taken in boarders to make ends meet. After he died, most of his personal items were auctioned off and a $64.00 check from the proceeds given to Laura. Later, according to his great-granddaughter, Libby Kephart Hargrave, a house fire at Laura Kephart’s home destroyed most of her husband’s personal letters and his diary. What few letters did survive indicate that his wife stoically accepted her husband’s trials with alcoholism and allowed him the freedom he needed to continue writing. According to his great-granddaughter, his wife Laura never spoke an unkind word about him to her children and did not protest when he took off for the Smoky Mountains.[ii]

Details of his personal life and relationship with his family remain elusive. Horace and Laura may have purposely made sure their private communications were not discoverable. The lack of primary material renders it difficult for biographers to draw conclusions about their unconventional marriage arrangement. What is obvious is that his stature as a husband and father were secondary to his place in history as the man who spearheaded the development of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Alarmed at the rate of clear-cutting and habitat destruction he was witnessing in the mountains, Kephart used his status as an author to advocate for a national park. He lobbied politicians and wrote letters and articles for the papers and outdoor magazines extolling the beauty of the area, promoting the need to preserve the mountains as a national treasure.

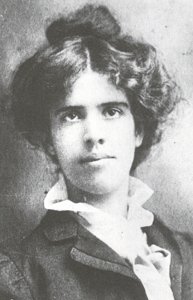

The personal life of Emma Bell Miles, on the other hand is well scrutinized. She left a diary chronicling her inner turmoil and familial hardships, transcribed and edited by Steven Cox in a book titled Once I Too Had Wings (2014). Emma’s parents were both teachers in Signal Mountain, Tennessee, north of Chattanooga. She pursued an art education in St. Louis, Missouri but only lasted two years before becoming homesick for the mountains. When she returned home, she married a local man named Frank Miles. They had five children. Over-burdened with the responsibility of raising five children on little income, she was constantly at battle with her husband to carve out time to write and draw. Her need to pursue art was utilitarian, driven in part by her family’s desperate financial conditions.

Emma Miles had a following of wealthy patrons who paid for her art in the form of sketches, cards, and watercolors. Her diaries reveal she continuously turned to her wealthy patrons to support her and her family. These patrons were mostly fashionable women from cities like Knoxville, who had vacation homes in the mountains. Many were fond of Emma but she reveals that a few were weary of her constant appeals for money. When Emma’s three-year-old son Merick contracted Scarlet Fever, the family could not afford to pay $10.00 for a doctor. When Merick died Emma never fully recovered emotionally. Reading her diaries is heart wrenching. She had a deep-seated resentment and at times loathing, toward her husband. “He demands his right and I give as far as possible…I am the drudge, the ragged, pinched, worn-out slave….Oh the pity I have missed – half of a life!”[iii]

She lost her job working for the Chattanooga Newspaper when she revealed to them that she was pregnant. Her diaries hint of her desire to be free of the conjugal demands made by Frank because of the inevitable outcome. Stating: “God forgive me for bringing into the world children I cannot take care of…” and later, “I have decided not to put off the murder that must be done…”. Although many pages of her diaries were ripped out, there is speculation she may have resorted to herbal remedies to self-abort.[iv]

When Emma contracted tuberculosis, she begged her husband to allow her the freedom and time to rest and complete some of her artistic projects. “Would it not be better to go where I can have my health and do my work?”[v] Frank reluctantly allowed Emma the opportunity to rest in the town homes of wealthy patrons but demanded her presence when he felt overwhelmed or burdened with domestic life.

From reading their works, it is apparent the lifestyle Horace Kephart chose suited the cultural norm in rural Appalachia at the time. Not many would make similar allowances for Emma Bell Miles. Abandoning her family to pursue her art was out of the question. In fact, Frank and his family never understood Emma’s independent nature. Emma describes Frank’s condescending comments about her running around with a different class of people and that the mountain people disliked her for it. By contrast, Horace Kephart’s wife, Laura, both forgave and came to a grudging acceptance of her husband’s wanderlust. In letters she wrote to her children, she proclaimed her love for her husband to the very end and her commitment to remain married.[vi]

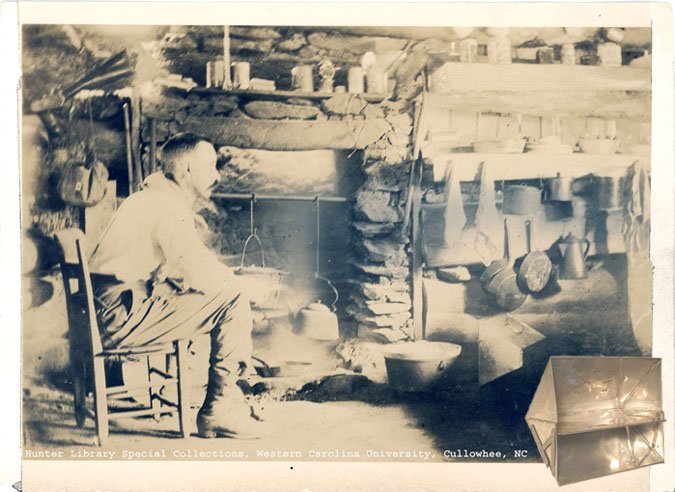

Given their domestic situations, it is no wonder then that the authors’ interpretations of household life and the roles of husbands and wives varied. To his credit, Horace Kephart observed the patriarchy and the lack of chivalry men showed towards their wives. He explained that husbands expected to be fed first while their wives waits to be seated. When the men were away hunting or fishing, the women tended to the daily chores, such as cutting wood for the fires, planting in the fields, taking care of the children. Common courtesies toward women were non-existent. He chalked it up to the culture: “…it is seldom that a highland woman complains of her lot. She knows no other.”[vii] Kephart admitted that the role of a wife was no more than that of a “…sort of superior domestic animal” although he did not go so far as to explain why this may be abhorrent. Rather he claims, “…the average mountain home is a happy one, despite the low standards of living.”[viii]

Emma Bell Miles had a lot to say about the situation in which wives found themselves. Her interpretation focused on the one thing women should complain about: subjugation. Although addressing the ways of men in The Spirit of the Mountains, her narrative reflected the advantageous freedom afforded to men such as Kephart. “He is tempted to eagle flights across valleys…His ambitions lead him to make drain after drain on the strength of his silent, wingless mate…” while it is “manners for a woman to drudge and to obey. All respectable wives do that.” One can imagine Emma’s frustration with the situation facing women in her circle because she had lost her ‘wings’, tethered to a home life she found untenable. As she puts it, while men were allowed to roam freely over the mountains in pursuit of game or for the sheer joy of wilderness adventure, women were spending “…long nights of anxious watching by the sick, or waiting in dreary discomfort.”[ix]

One thing the authors do agree on is the impact the hard life had on mountain women. Teenage marriage and pregnancies wreaked havoc on women’s health. This, combined with the hardships of toiling in the fields and home, aged the women more so than men. Kephart observed that “…frequent child-bearing with shockingly poor attention, and ignorance or defiance of the plainest necessities of hygiene, soon warp and age them.”[x] As a woman, Miles was more forgiving. In her diary, she said, “You will hear plenty of people say that I grew old before my time; Daughter the reason some women look young at forty-five is that they have never lived.”[xi]

Other aspects of Appalachian life where the authors agree was the impact outsiders had on the culture, including the wealthy patrons they depended on and industrialists. Emma poses the uncomfortable truth that many of the people who were her patrons—tourists— were also gawkers. In one emotional scene from The Spirit of the Mountains, she described how the religious ceremony of Baptists’ foot washing was becoming a tourist attraction. She recalled how the ‘city folk’ who were ‘pressing in’ on the mountains, showed up as spectators to foot-washing events. And, she stated, it was especially unbearable for the women who were uncomfortable with these outsiders watching their ceremonies.

Miles explained how the summer tourists were building cottages or staying at the hotels and hiring the locals. “The pure air, the mineral waters, are advertised abroad and the summer people begin to come in….Good roads are built in place of creek beds and rubber-tired carriages whirl past the plodding oxen and mule teams.”[xii] She felt the pull of civilization and questioned whether it was good or bad. The ‘old mother’, she laments, seeing how much easier it is to buy cloth instead of hand spinning, casts the loom and wheel aside relegating it to the barn loft.

As an insider looking out, Miles’s narrative seems to be one long contemplation on what could be. Indeed, she both loved and hated her existence. In her diary’s entry dated 1909, before the death of her son Merick and her marital troubles, she exclaims, “Life, life, life: everywhere thrilling to million tinted splendors of growth, of procreation, of abundance and beauty. Oh home! Oh forest loom of life stuff! Oh holy world!”[xiii]

As time passed Emma’s joy for mountain living was not enough to sustain her happiness. Perhaps she was aware that no matter how hard she may try she would never be viewed as being in the same class as her patrons. Maybe she felt her art was the avenue available to elevate her status. One can’t help but think she was speaking of herself when she claims in Spirit of the Mountains, “Is it any wonder that false ambitions creep in?” and “…throughout the highlands…our nature is one, our hopes, our loves, our daily life the same, we are yet a people asleep, a race without a knowledge of its own existence.”[xiv]

For Horace Kephart, the transformation taking place in Appalachia was a loss of manliness and the “…hard-earned patrimony...” As corporations moved in and destroyed the environment to suit their industrial needs, the mountaineer was forced to leave and move to an uninvaded place where “he will not be bothered” by outsiders. “Then it is good-bye to the old independence that made such characters manly.” Interestingly, Kephart championed the development of a national park, which meant many of the mountain families he studied would be asked to leave—or forced out—through eminent domain. Yet in Our Southern Highlanders, he disdained the lumber and mining operations and the people who ran them, stating the “…invading civilization…is composed of men who care nothing for the welfare of the people they dispossess.”[xv]

Not surprisingly, Emma Miles and Horace Kephart proclaim that education would save the southern highlanders and was the only way to prevent a catastrophe. Both authors believed that education in trades and skills would save the mountain culture from extinction brought about by dislocation. Emma Miles is especially cautious because she knew first-hand the lure of wealth and comfort before her own family life soured. “The value of money, the false importance of riches, is evident to their minds before the need for education.”[xvi] But even here their viewpoints mimic the limits gender place on achievement. In what now appears ironic, Kephart quoted Miles in the last chapter of his book. “Must this free folk who are in many ways the truest Americans of America be brought under the yoke of caste division, to the degradation of all their finer qualities, merely for the lack of the right work to do?”[xvii] And while Miles referenced women toiling over tubs of water whose talents might be better served if they were able to sell woven coverlets, rugs and quilts, Kephart warns that even the most backward of men held “sterling qualities of manliness” that our nation could not afford to waste. The schools, he believes, should be turning out good farmers, mechanics and housewives.[xviii]

Both authors died before achieving everything they set out to accomplish. Emma Bell Miles died of tuberculosis in 1919 while working on her last book, Our Southern Birds, published soon after her death. Her diary indicates she was working on manuscripts never published and now lost to history. As her children aged, they became more independent, and her popularity as an artist and writer grew. If she had lived longer, she may have seen some of her other works progress to fruition. Horace Kephart died in an automobile accident in 1931, before realizing his dream—the founding of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Likewise, he left behind an unpublished manuscript, Smoky Mountain Magic, which was miraculously not lost in the family’s house fire and published eighty years after he wrote it.

One has to wonder what Emma could have accomplished and how different her biography might be had she lived longer and been afforded the same opportunities as Horace. Horace had the luxury of being 1) a man, and 2) an outsider. His contemporaries romanticized him. He was constrained only by familial commitments miles away that never tarnished his reputation as a writer. Emma’s life was the tragic existence of an artist constrained by gender and poverty. Horace Kephart watched as civilization advanced into the mountains and shunned it just as he shut the door on his personal life to appease his adventurous spirit. His desire for a National Park was the epitome of his philosophy that the Appalachian manly culture would wither without preservation of its wild places. Emma Bell Miles also recognized the rapidly changing environment around her, but rather than shut it out, she welcomed opportunities to define her place in it.

NOTES

[i] George Ellison and Janet McCue. Back of Beyond: A Horace Kephart Biography. Great Smoky Mountains Association. 2019.

[ii] Hargrave, Libby Kephart. "Introduction." In Smoky Mountain Magic, by Horace Kephart. Great Smoky Mountains Association. 2009.

[iii] Miles, Emma Bell. Once I Too Had Wings: The Journals of Emma Bell Miles 1908-1918. Kindle EPub. Ohio University Press. Ohio University Press. 2014.

[iv] Miles, Once I Too Had Wings, Loc 345

[v] Miles, Once I Too Had Wings, Loc 1600

[vi] Hargrave, Introduction.

[vii] Kephart, Horace. Our Southern Highlanders. The Internet Archive. MacMillan Company . New York: The MacMillan Company. 1922. 332

[viii] Kephart, 332.

[ix] Miles, Emma Bell. The Spirit of the Mountains. The Internet Archive. James Pott & Company . New York: James Pott & Company. 1905. 168

[x] Kephart, Horace. Our Southern Highlanders. The Internet Archive. MacMillan Company . New York: The MacMillan Company. 1922. 288

[xi] Miles, Once I Too Had Wings, Loc 1210

[xii] Miles, The Spirit of the Mountains, 190.

[xiii] Miles, Once I Too Had Wings, Loc 902

[xiv] Miles, The Spirit of the Mountains, 201.

[xv] Kephart, Our Southern Highlanders, 456.

[xvi] Miles, The Spirit of the Mountains, 198.

[xvii] Miles, The Spirit of the Mountains, 198.

[xviii] Kephart, Our Southern Highlanders, 456.

Sheila Myers is a professor at Cayuga Community College in Upstate, NY. She’s an award-winning author of a historical fiction trilogy about the Durant family who pioneered the Transcontinental Railroad and the Adirondack wilderness during the mid-late 19th century. Her affinity to mountains led her to the Great Smoky Mountains National park where she was first acquainted with the writings of Kephart and Miles. Her novel, The Truth of Who You Are, based on the stories of the people who once inhabited the park and published by Black Rose Writing, launched in April, 2022. You can find out more on her website https//www.sheilamyers.com