Appalachia and the Quest for a “Viable Alternative”: The Macedonia Cooperative Community, 1937-1958

By Luke Manget

In the spring of 1937, a Columbia University professor of education named Morris Mitchell arrived in the mountains of north Georgia with a vision for a new way of organizing rural life. Having purchased a few hundred acres in the Shoals Creek valley of Habersham County, he began to carve his vision out of the landscape. The Macedonia Cooperative Community was incorporated as a joint-stock company, and all members—a small number of families at first—owned shares in the company. Within a few years, it would contain several homes, private gardens, and an array of common lands, including fields, pastures, forests, lakes, and streams. It would also include common property, such as rental cottages, barns, and garages. Eventually, the community would have a school, museum, and art gallery. Members would develop a diversified agricultural economy based on dairy and truck farming, and they would market their produce and purchase seed, fertilizer, and implements through cooperatives. They would sell honey and furniture that they would build in a small craft shop. Inspired by the Tennessee Valley Authority, Mitchell wanted to build a dam on Shoals Creek that would provide electric power. He hoped Macedonia would serve to demonstrate to rural Appalachian people—and, indeed, rural people nationwide—the benefits of cooperation.

A cabin at Macedonia. Photo by Edward Orser, 1975.

Mitchell was part of a network of academics, missionaries, politicians, and businessmen that embraced what I call the community ideal as a basis for reforming rural life. An outgrowth of the Country Life Movement, this movement reached its height in the interwar years before virtually disappearing during the anti-communist hysteria of the 1950s. They identified myriad problems with rural life and sought to solve them holistically, an approach that ultimately led them toward the goal of creating model utopian communities. Macedonia was to be one experiment in the broader quest to find what Edward Orser has termed “a viable alternative” to prevailing ways of organizing society.[i] That quest has been all but abandoned.

Southern Appalachia has attracted an outsized share of social reformers, dreamers, and visionaries eager to show mountain people and the rest of America a better way to live. In the first three decades of the twentieth century, a wave of reformers turned to western North Carolina to find a viable alternative. People like John C. and Olive Campbell, James McClure, Arthur Morgan, Howard Kester, and Morris Mitchell were attracted to the region because they saw both a benighted people in need of economic and social uplift and a noble people possessed of the “sturdy” characteristics of pioneers. Their attitude toward the mountaineers was a mixture of empathy, pity, scorn, curiosity, and appreciation, all colored by a somewhat paternalistic worldview. Many of them believed that if they could teach locals how to organize cooperatively, they could establish a more democratic path to economic development. And so they flocked to the region, preaching the gospel of cooperation.

In 1926, for example, Olive D. Campbell established the John C. Campbell Folk School in the mountains of Clay County, North Carolina, which initially focused on teaching improved agricultural methods and cooperative business principles. Under Campbell, the school established a dairy cooperative, a credit union, and a craft guild, and it held weekly dances, concerts, and festivals aimed at bringing the community together. These reformers were progressives in that they believed in progress over tradition, but they sought to chart a very different path to progress than the one the region ultimately followed. On their path, economic and political power was decentralized and more democratically distributed. They believed rural communities needed to become more efficient, but they believed that efficiency was not incompatible with a more moral and democratic system. They way to reconcile them was through cooperation. “Cooperation is a direction,” Mitchell proclaimed, “the opposite direction from competition. The individual gains through, not at the expense of, general welfare. Fear and greed are basic to competition; love and generosity to cooperation.”[ii] Because they saw in the mountains an agrarian refuge where Jeffersonian ideas of landed independence, self-sufficiency, and egalitarianism still held sway, they felt it was the perfect place to implement their vision for a cooperative society.

Upon returning from the western front in 1918, Mitchell took a part-time job picking fruit at an orchard and then as principal of a small school in Richmond County, North Carolina, where he began to formulate his philosophy of education. In five years, he and his students turned the school into a force for community organization, starting gardens, forming cooperatives, and addressing social, health, and environmental problems. In 1924, he left his job as principal to study education in graduate school. After a brief stint at Columbia University, where he studied under John Dewey, he earned his PhD from George Peabody College for Teachers (now part of Vanderbilt) in Nashville. Mitchell was impressed by Dewey’s idea that education could be a powerful tool of social reform if it was functional; that is, if it was aimed at solving community problems. In 1934, he took a faculty position in Columbia University’s New College, and two years later, he accepted a temporary position with the New Deal’s Resettlement Administration. In these capacities, he maintained vigorous correspondence with many of the movement’s leaders and served as a consultant for several cooperative ventures. In the summer of 1935, he helped establish New College Community near Canton in the mountains of Haywood County, North Carolina, where students spent summers learning how to live in a cooperative community. In 1937, he purchased the land that would become Macedonia in the north Georgia mountains. Throughout his early career, Mitchell promoted education as a way to solve community problems through cooperation.

Mitchell was attracted to southern Appalachia for at least two reasons. First, he believed that due to the poverty of the region, the region was in great need of structural reform and would hopefully be open to it. He largely blamed exhaustive agricultural practices for the region’s poverty, and he believed that individual farms on sub-marginal lands should be replaced by collective farms on the fertile bottomlands that could invest in better technology, machinery, and fertilizer. The creation of cooperatives, credit unions, and community-owned craft industries would allow communities to boost their income levels and improve their quality of life. Perhaps realizing that locals might not be too receptive to such wholesale changes, he advocated the reform of mountain culture. He sought to enlist the help of schools and churches to teach the gospel of cooperation, and he hoped to establish adult education programs “to awaken awareness of the place of the valley in the whole social and economic structure.”[iii]

Second, Mitchell romanticized the region and its inhabitants. While he believed that they were in desperate need of reforming, he was impressed by their pioneer existence and viewed the small farms and the mountain landscape as picturesque. “These people are poor in the material things in life,” he told his students at New College Community. “Yet they are rich in philosophy and folk lore that is almost untainted by city influence.” He added that “Sunsets, cloud effects, picturesque buildings, and people in a beautiful mountain setting provide rich material for the artist.”[iv]

As an experiment in cooperative living, Macedonia lasted twenty years and was moderately successful. In his well-researched Searching for a Viable Alternative: The Macedonia Cooperative Community, 1937-58, Edward Orser argues that the community did improve the material lives of its members. Until the end of World War II, the community was small. Just four families, all of whom were local farmers, comprised the first wave of settlers, and they undertook the labor of building community buildings, a saw mill, clearing land, and establishing gardens. Although Mitchell intended to create a more democratic system of governance, he remained a somewhat paternalistic overseer of the project who did not live in the community full-time. Orser contends that community members did not fully buy into the cooperative ideal, seeing the community as a practical way of improving their material well-being. But that changed during World War II when the community underwent a significant change. Mitchell’s pacifist views placed him at odds with Macdeonians and the people of north Georgia, and by 1945, the locals had left the community as a group of pacifists flocked to it, injecting new life and new direction into the community. Almost overnight, it became a pacifist colony, filled with men and women from outside the region who saw the community as a way to implement their pacifist ideals. “Cooperation is applied pacifism,” they asserted. In 1948, they drafted a new statement of purpose. It said:

“So, to the viciousness of the contemporary pattern of people, machines and money concentrated in too few places and controlled by too few men, we offer as a positive alternative small groups of people operating within a framework of cooperation and mutuality, owning and controlling their own small shops and farms, building among themselves socially, culturally and recreationally a way of life in which men may be peaceful, free, and creative members of the human family.”[v]

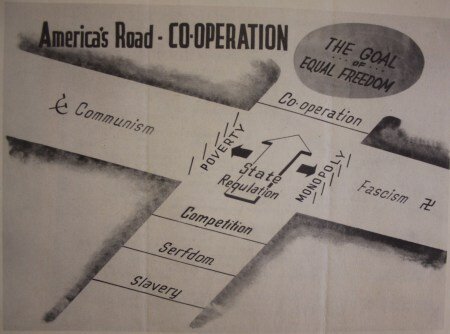

During the chaotic years of the Great Depression, some Americans came to see cooperation as a way to solve the nation’s economic problems while avoiding the polarizing tendencies of fascism and communism. From Morris Mitchell Papers, UNC-Chapel Hill.

The newly arriving pacifists had little to no material assets to bring to the community, and Macedonia struggled through the late 1940s to produce income. However, many Macedonians found community life purposeful and exhilarating, and they succeeded in improving the community by building community centers, dormitories, playgrounds, and more. By 1954, the group had established a business model for creating wooden toys and found markets in the urban northeast, including F.A.O Schwartz. Things were looking up, but at the same time, the philosophy behind Macedonia also began to change. Orser contends that social pressure began to mount on members to conform more to a more homogeneous and unified identity. After coming into close contact with a group of religious communitarians called Bruderhof, they even added a religious aspect to their statement of purpose. It said: “We believe in all prevailing spirit of Love and Goodness and recognize the existence of a creative power at work that is the source and maintenance of all life.”[vi] Many felt that in order for a community to property function, they needed a deeper connection to each other rooted in common spiritual beliefs.

By 1957, Macedonia was falling apart. Fire and illness played a role in weakening it, but the community ultimately could not reconcile its demand for community cohesion with the need for individual identity. As one influential faction pushed for greater cohesion, some left the community, and by 1958, those who remained at Macedonia moved north to New York and joined the newly created Bruderhof community. They took their toy-making business with them, and today, that business continues strong as Community Playthings, Inc., which sells wooden playgrounds, playscapes, and toys to schools, local governments, and individual consumers. However, the cooperative community principles that once infused the business are no longer maintained.

The remains of the toy workshop at Macedonia, where community members made toys to sell. Photo by Edward Orser, 1975.

These kinds of utopian experiments have almost entirely fallen out of favor with the American public during this neoliberal age. While the intentional community movement continues to search for viable alternatives, it has no longer has the influence over progressive political and academic discourse as it did in the first half of the twentieth century. Although I am too individualistic to think I would have joined one of them, I do think that they spoke—and continue to speak—to many Americans’ ongoing search for community in an economy that erodes the health and viability of geographical communities. The “creative destruction” of capitalism, to use the words of Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter, undermines the stability of rural communities. Macedonia and other experiments like it were an attempt to reconcile the need to engage in broader markets in order to improve material well-being with the desire for long-term stability and democracy, but they had serious drawbacks as a viable alternative to competitive capitalism. In short, they attempted to codify, plan, and make permanent something that resists such structure. Community is, or should be, an organic phenomenon. It changes and evolves as people change and evolve. The Macedonia Cooperative Community raises the question of whether or not such reconciliation is possible, and if it is, what level of planning is required?[vii]

[i] W. Edward Orser, Searching for a Viable Alternative: The Macedonia Cooperative Community, 1937-58, American Cultural Heritage 6 (New York: B. Franklin, 1981).

[ii] Orser, 62.

[iii] “Preparing for a Summer at New College Community,” May 1936, Morris Mitchell Papers, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Orser, Searching for a Viable Alternative, 108.

[vi] Orser, 198.

[vii] For more on experimental communities, see Paul Keith Conkin, Tomorrow a New World: The New Deal Community Program, (New York: Da Capo Press, 1976); George L. Hicks, Experimental Americans: Celo and Utopian Community in the Twentieth Century (University of Illinois Press, 2001).