Tapping Into History with Maps: Maple Sugaring in Southern Appalachia

By luke manget

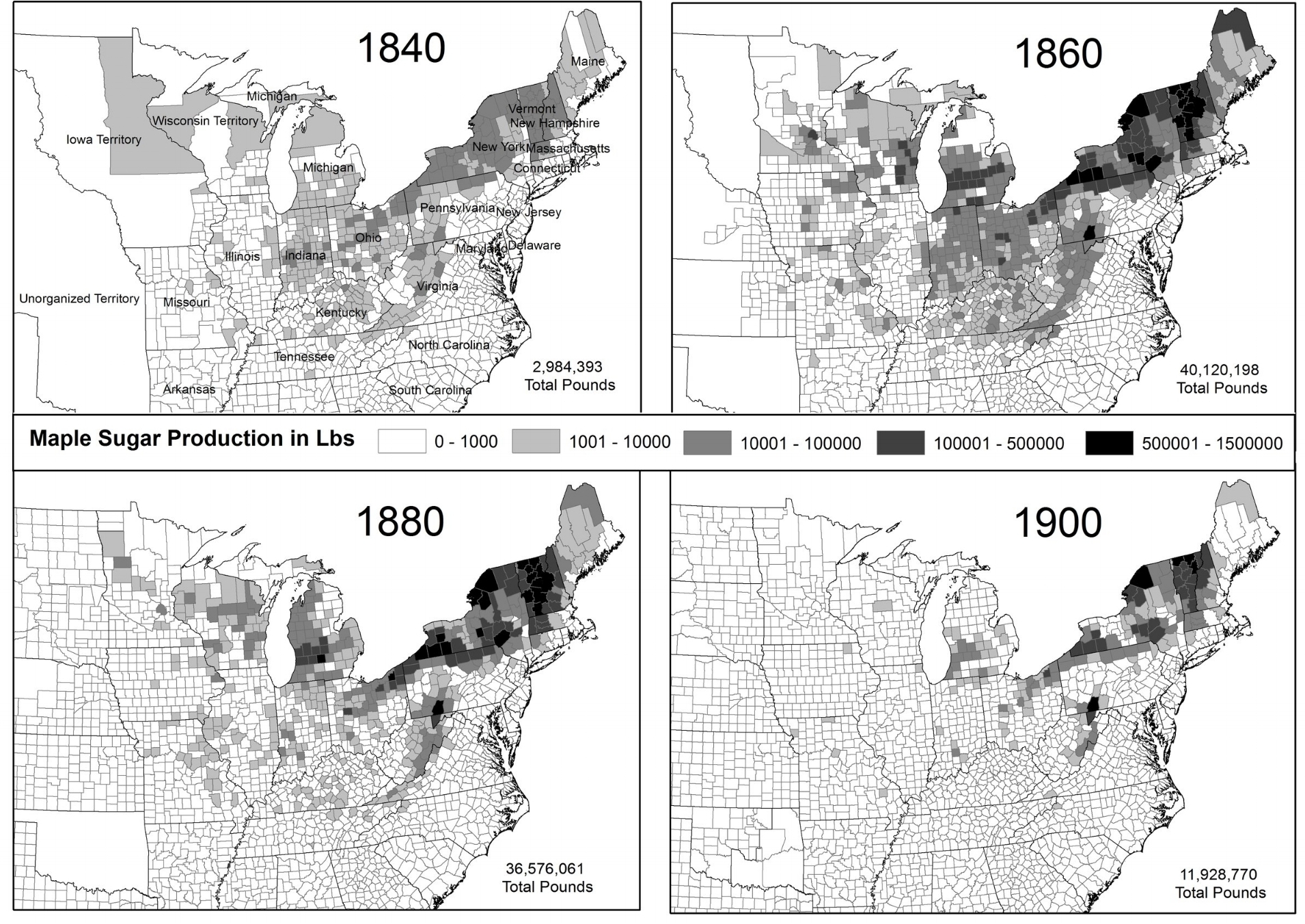

This map tells a fascinating story: the rise and fall of the maple sugar industry. Due to effective branding by the modern industry, most people associate maple sugar and maple syrup with Vermont, but as you can see, at the industry’s height in the mid-nineteenth century, it stretched down into Virginia and northwestern North Carolina. To many farmers and politicians, it held great promise as a domestic source of saccharine, and rural people found it a profitable pursuit in the mountain forests. The future looked bright. By the end of the century, however, maple sugar production was dwindling, and by the early twentieth century, it was close to nothing. Growing imports of cane sugar and the rise of sugar beet farms in the West brought the cost of sweetener down. As maple sugar became a luxury item, maple-tappers—mostly small farmers—found fewer profitable markets for their wares. In addition, deforestation and other environmental changes reduced the size of sugar maple stands in the eastern U.S.

Tapping a sugar maple, ca. 1905.

But this map tells a more complicated—a more human—story. It tells of a shift in the way mountain people interacted with the forests, the decline of a particular way of life.

In the early nineteenth century, sugar maples (acer saccharum) were found in large stands growing throughout the northern United States and Canada, from Minnesota in the west to Maine in the east and North Carolina in the south. After learning of the process of making maple sugar from Native Americans in the late seventeenth century, French and English colonists developed a thriving industry by the late eighteenth century. Because they favor climates with cool maximum temperatures in the summer, sugar maples are typically not found in the South, but they thrived in the cool, high altitude climate of the southern Appalachians. William West Skiles, an Episcopalian missionary in the northwestern North Carolina hamlet of Valle Crucis, noted in the 1840s that some stands stretched over 50 acres and were “as luxuriant as any in the northern Alleghanies.”[1] In addition to providing Native Americans and newcomers with sweetener, sugar maples play an important ecological role in northern hardwood forests, as they serve to redistribute water from deeper moist soil layers to shallower, drier soil layers in a process called hydraulic redistribution that benefits all plants underneath its canopies. One aging eastern Kentucky farmer swore in 1898 that ginseng grew best on “sugartree lands.”[2]

Boiling down the sap from a sugar maple, ca. 1905.

While the production of maple sugar never approached the volume of cane sugar in Louisiana, involvement in the production process was much more widespread. In Louisiana, cane sugar was produced by African American slaves and fostered the development of a highly stratified and violent social order. Maple sugar was different. Up and down the Appalachian spine, maple sugar was produced by an army of independent small farmers, typically as a supplement to their farm production. It was a much more democratic resource. In 1862, the U.S. Commissioner of Agriculture reported that “the demand for maple sugar has increased with the manufacture of the article, so that at the present time there is a ready market for all that is made at very remunerating prices; thus affording profitable employment to a large portion of farmers at a season of the year when little else can be done in the other departments of farm labor, and wherever the business is extensively and skillfully carried on making it one of the largest and most profitable branches of agricultural industry.”[3]

In the early nineteenth century, the process went something like this: in the late winter or early spring when the sap was “running,” that is, when nighttime temperatures dipped below freezing and daytime temperatures were warm enough to thaw the sap, a tapper would find a stand of sugar maples and make incisions in the bark of the tree that looked like a “V.” Then, he would split and hollow a log of soft wood to use as a trough and hammer in a piece of iron that looked like a carpenter’s gouge to convey the sap to the trough. As the sap flowed down the tree in the inner bark, the trough filled, and the tapper would empty the sap into an iron kettle in which it was boiled on an open flame. By the mid-nineteenth century, tappers had replaced wooden troughs and iron gouges with tin buckets and steel augers, and they were constructing “sugar houses”—crude structures that protected the boiling sap from debris and other impurities. The sugar-maker boiled the sap continuously for several hours until the sap was reduced to a thick, grainy syrup. Then the syrup was removed from the fire and allowed to cool in pans made of sheet iron and copper. Excess syrup was drained into tubs as the sugar was stirred until it was “sugared off.” In the early days of American settlement in the midwest, some settlers ate “sap porridge” made from mixing corn meal with crude maple sugar and molasses.

Sugar maples in the fall.

Maple sugar was one of several forest commodities that helped sustain rural Appalachian communities. Due to the existence of a complex web of use rights that established popular access to forests regardless of who owned the property, rural people could venture into forests that they did not own and find so-called “sugar orchards” where they would set to work tapping the larger trees that were often over 300 years old. Store records from a merchant in southeastern West Virginia reveal that locals bartered significant amounts of maple sugar to obtain goods. Nearly 20 percent of Ely Butcher’s barter business was in maple sugar.[4] In 1860, a writer traveling through the mountains of east Tennessee stayed with the family of a renowned hunter whose wife made maple sugar that was “so thoroughly clean and white that it has lost the distinctive taste of tree-sugar.” Illustrating the racism pervasive in the mountains, she claimed to have bought “store sugar” once before, but she didn't like it. "I have never used any sugar made by them nasty niggers sence."[5]

Some women were able to sell maple sugar and maple syrup as a means of financial independence. Sometime in the 1830s, Watauga County (NC) native Betsy Calloway married a recent arrival from Kentucky named James Aldridge, who quickly developed a reputation for being a great “marksman, trapper, and backwoodsman.” For close to fifteen years, he lived with his family in a small cabin under the Grandfather on Hanging Rock Ridge, having seven children with Calloway. However, a woman arrived from Kentucky, claiming to be Aldridge’s real wife, and that revelation destroyed his relationship with Betsy. Calloway took to digging ginseng and other roots and selling maple sugar to develop financial independence from Aldridge. She worked several sugar orchards across the mountains and sold maple sugar for ten cents a pound and maple syrup for ten cents a gallon. Aldridge eventually left her, but with the proceeds of ginseng and sugar, Calloway purchased clothes and other necessities, kept a comfortable house, and, according to the memory of the old-timers, “took care of all preachers who came to her home.”[6]

In the closing decades of the nineteenth century, however, changing markets for sugar and the arrival of large-scale timber companies brought a decline in the maple sugar industry in southern Appalachia. In anticipation of the profits to be made from hardwood forests, large landowners began protecting their trees, prosecuting those trespassers who damaged their standing timber. This decline was part of a broader enclosure of the commons that also targeted the open livestock range, medicinal herbs, game, and fish. Over the next few decades, laws were passed at the state level prohibiting these resources from being removed from private property. Furthermore, as forests were clearcut across western North Carolina in the opening decades of the twentieth century, sugar maple stands entered a decline from which they have not recovered, having been outcompeted during regeneration by faster growing species such as poplars.

While making maple sugar for home consumption continued to be an important part of mountain life well into the twentieth century, it never quite held the economic promise that it did in the mid-eighteenth century. And the de facto commons—that is, the commons created by tacit and ongoing negotiations between private landowners and forest users—dwindled, forcing people to rely more heavily on wage work and private farm production.

[1] Susan Fenimore Cooper, ed., William West Skiles: A Sketch of Missionary Life at Valle Crucis in Western North Carolina, 1842-1862 (New York: James Pott & Co., 1890), 43.

[2] Elisha Bird to Harrison Garman, 31 October 1898, Fol. 5, Box. 13, Harrison Garman Papers, University of Kentucky.

[3] U.S. House of Representatives, Executive Document 78, 37th Cong. 3rd Sesson, Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture for the Year 1862 (Washington: GPO, 1863), 394-395.

[4] Ely Butcher Store Account Books, Randolph County, 1841-1883, West Virginia State Archives, Charleston, West Virginia.

[5] R of Tennessee, “A Week in the Great Smoky Mountains,” The Southern Literary Messenger, August 1860.

[6] John Preston Arthur, A History of Watauga County, North Carolina: With Sketches of Prominent Families (Easley, S.C.: Southern Historical Press, 1976), 190.