The Stories We Tell Ourselves:

Proctor, Cataloochee and the Pursuit of Environmental History

Remnants of the town of Proctor, Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Photo by Luke Manget

By luke manget

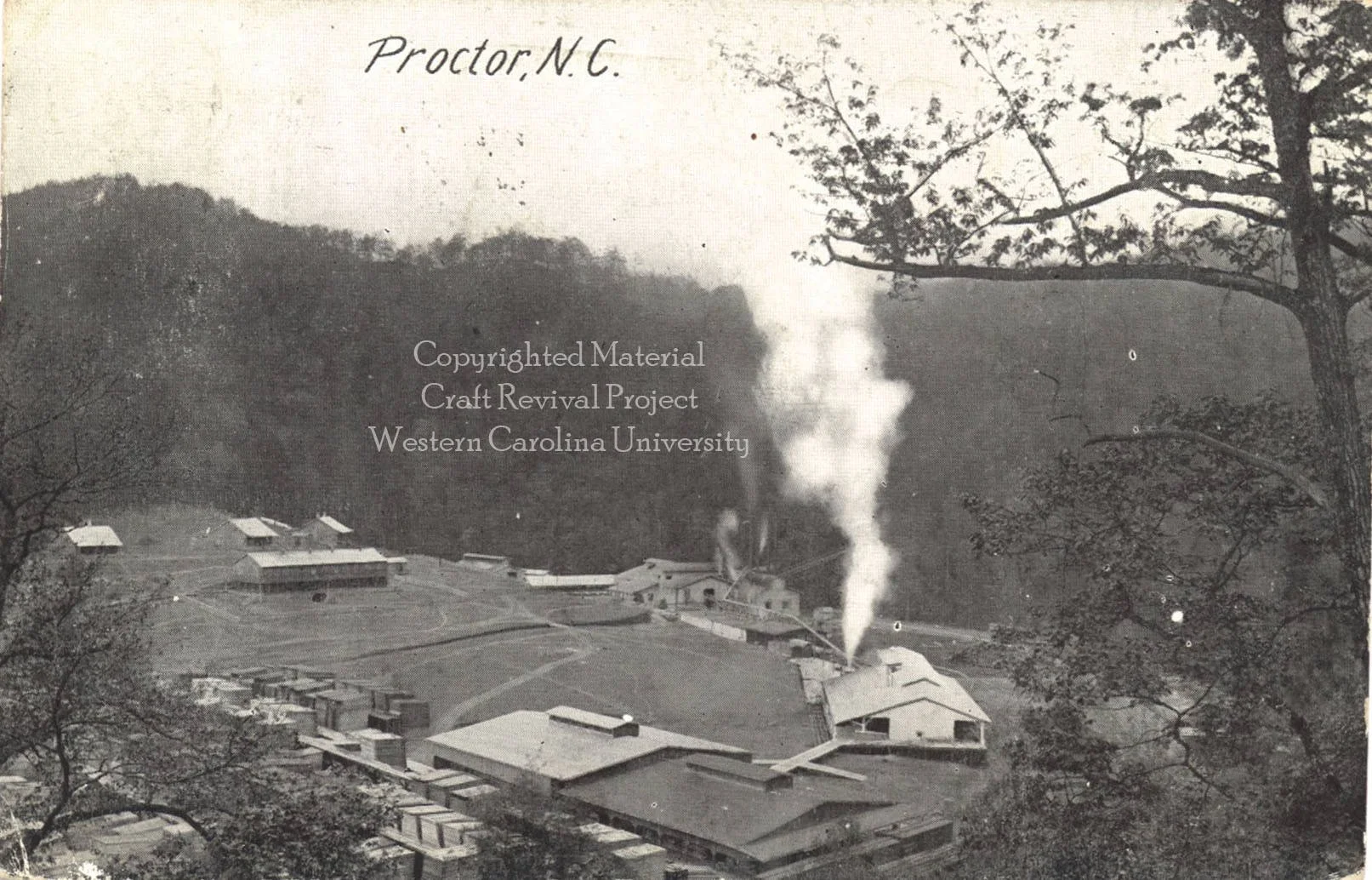

Getting to the abandoned town of Proctor requires some hiking nowadays. You can either take the Lakeshore Trail some 15 miles from Fontana Dam into the remote southwestern corner of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, or you can boat across Fontana Lake and up the long mouth of Hazel Creek, cutting off 10 miles of hiking. Five miles down the old logging railroad grade, you first come upon it. At first, you might not see the remnants of old foundations. Mosses and ferns camouflage them, and medium-sized trees grow in their midst, but the discerning eye can make out the evidence that a town of some 1,000 souls once bustled with activity there. Although the area had been home to a small farming community since the mid-nineteenth century, the town of Proctor was created by a Pennsylvania lumber company, W. M. Ritter & Co., in the first decade of the twentieth century to operate a large sawmill. Ritter extended the Smoky Mountain Railway into Proctor and even generated electricity from a coal-powered plant.

On the opposite end of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, tucked in the northeastern corner, is an abandoned settlement remarkable in its conspicuousness. In fact, like the more popular Cade’s Cove, many of Cataloochee’s main community buildings have been meticulously preserved by the park service. Tourists can drive through the valley, past churches, school houses, homes, and mills. A self-guided tour introduces motorists to the prominent families of the valley, their primitive lifestyles and quaint culture. They hear about quilting bees, corn shucking, barn raising, tooth jumping, hunting bear, driving mules, and fishing for trout in what can only appear to the visitor as a modern-day Eden. Indeed, motorists hear an inspiring story of a pioneering community struggling to wrest a living out of the rugged wilderness. If you’re lucky, you might see elk grazing in the meadow between buildings.

Cataloochee Valley has been used by humans for millennia, but Euro-Americans first settled the area in the 1820s. Population grew slowly and sporadically, and by 1910, the valley contained 1,250 residents, surpassing Proctor as one of the largest settlements in the Smoky Mountains. Most Cataloochee residents refused to sell their land or their timber rights to extractive companies, so it remained an agricultural community, if a steadily weakening one, until the park service coerced them to sell in the 1930s.

The communities of Proctor and Cataloochee could hardly be more different. One has largely been reclaimed by the forest; one is diligently maintained. One is publicly forgotten; the other is commemorated and memorialized. As historians, we must ask the difficult question: “Why?” Why did these two communities meet such fates? Perhaps more importantly, why do we choose to memorialize one and not the other? In digging for answers, we can begin to explore the ways in which environmental history can contribute to our understanding of the past. When we as environmental historians look at the past, we look for different things than do other historians. All historians approach the past with some presentist agenda, but we are loosely united by the belief that the pace and nature of environmental change offers a formidable challenge to modern human societies. As such, we examine the past in order to understand the changing relationships between humans and the rest of nature, so that we may provide parables that can inform the important debates regarding the sustainability of the human race.

For clarifying purposes, I might reduce the main lines of environmental historical inquiry into three questions for which Proctor and Cataloochee can offer illustrative answers:

How have particular environments shaped the experiences of individual people and determined the outcome of historical events? This may seem obvious, but historians have traditionally overlooked, if not outright ignored, ecological forces in the human story. In the cases of Proctor and Cataloochee, these forces are hard to miss. Sunlight, climate, and soil—filled with living and non-living organisms—dictated the crops that could be grown in the remote valley. Mammals, insects, and birds determined what would remain growing until it could be harvested. The giant forests that once covered the mountainsides influenced all aspects of life during the early years of settlement, from how houses were constructed to how successful hunting expeditions were to which medicinal plants could be found where. They also dictated the technological and labor regimes adopted by those loggers who lived and worked in Proctor. Those loggers were there in the first place to harvest forests on a massive scale. These interactions become part of what historians refer to as humans’ “dialogue with nature.”

Yet, local environmental conditions did not determine everything. The other half of an individual’s dialogue with nature came from the broader human community. When individuals interacted with nature by plowing, sowing, cutting, and moving, as well as hiking, photographing, and fishing, they brought to bear on the landscape the weight of enormous economic and cultural forces that transcended local ecosystems and swept the entire globe. To get at these forces, we must follow—to borrow a phrase from environmental historian William Cronon—the “paths out of town.” The second and third questions take us down those paths, but they differ in their emphasis on where they lead.

How have prevailing modes of production in a given society entered into human’s dialogue with nature? In our capitalist society, the follow-up questions might be: how and to what extent has capitalism and its associated values determined the way we interact with nature? How has nature shaped social relationships? How have class differences influenced the way in which individuals experience and/or interact with nature? Like so many settlements across the United States, Proctor was born an extractive industrial boom town. Some of its loggers probably came from surrounding farms, having decided that temporary wage work would help ease conditions on the farm. Others were part of an emerging industrial working class, wholly dependent on wage labor to survive. They lived in company owned housing, got paid in company issued currency, and purchased goods from a company store. They worked six days a week hauling old-growth trees out of the upper reaches of the Little Tennessee River watershed. But the activities of these loggers are a distant memory. Since the 1920s and the creation of the national park, most of the town has reverted back to early and mid-successional forest, and with each passing year, as the forests mature, the role it played in the industrial revolution becomes further obscured. It is now the permanent haunt of wildlife.

Proctor, NC, during its logging heyday, ca. 1920. Courtesy of Craft Revival Project, Western Carolina University.

Proctor existed to exploit resources, and it ceased to exist, in part, because the resource (trees) that called it into existence were no longer viable. Whether witting or not, the loggers who inhabited Proctor were agents of capitalism who had brought the forests into the giant industrial machine designed solely to convert nature into commodities.

Unidentified residents of Proctor, NC.

Cataloochee residents were also a part of this world system, although their role is more complicated than Proctor residents. Many of them attained a degree of self-sufficiency on their farms. Yet, no matter how much they tried to insulate themselves from the vagaries of the market, they still depended on it to some degree. They still purchased goods made across the oceans. They marketed their farm produce to timber workers and elsewhere outside of the region and, thus, felt economic hardship when the nation’s agricultural markets became increasingly dominated by mechanized and industrialized farms. Competition from the Imperial Valley in California, among other places, led to the decline of agriculture, which undercut the viability of the community. Whether they liked it or not, they too were part of an economy that was becoming global in scale. Indeed, through the story of their rise and fall, Proctor and Cataloochee can illuminate the ways in which communities—even seemingly remote ones—were shaped by global economic forces.

How has culture become a part of humans’ dialogue with nature? Economic considerations alone do not determine how individuals interact with nature. Culture—that is, the beliefs, myths, ethics, and laws that help humans make sense of the world—is adaptable and extremely powerful at shaping behavior. Gender, race, religion, and philosophy are key components of culture that can have a direct bearing on how individuals interact with nature. For example, cultural proclivities ensured that a gendered division of labor existed in places like Cataloochee. Women were responsible for tending the garden, rearing children, and harvesting medicinal plants from the forests, among other things. Men, on the other hand, hunted and fished, tended the cash crop fields, and performed much of the construction work.

The culture of capitalism predominated in the history of Euro-Americans’ relationship to nature, as people have always tended to see natural resources as a collection of potential commodities. Those individuals who ran Proctor were ensconced in this culture. On the other hand, the Cherokee, who used the Smokies as hunting grounds for millennia, believed that there was a normal flow of energy through all living and non-living things in the universe called To’Hi, and any upsetting of that flow could have disastrous consequences for humans. These beliefs had powerful ecological implications. Indeed, as the Cherokee case illustrates, culture can also served as a mitigating force, creating the conditions by which a conservation ethic develops. Environmental historian Richard Judd argues that conservation as an ideal developed among New England farmers’ commitment to democratic access to resources and a faith in common stewardship of the land. Facing demographic pressures, they regulated use of streams, pastures, and forests. Although they may not have all bought into the ideas of progressive conservation, residents of Cataloochee, like other Smokies’ residents, may not have subscribed wholesale to the culture of capitalism. They refused to sell their land to lumber companies, and many placed greater importance on stability, security, and community, rather than the values that capitalism rewards: profit-making and entrepreneurialism.

The conditions of these communities today—one as a forgotten community, the other as commemorated community—can also shine important light on the ways in which Americans have used myths in their dialogue with nature. As part of a collective historical memory that serves useful purposes, myths can reveal much about what Americans want to believe about their relationship with nature. The two most persistent myths involving the American environment are the agrarian myth and the wilderness myth, both of which can help explain the current conditions of Proctor and Cataloochee. In part, what makes places like Cataloochee and Cades Cove so appealing to tourists—and, conversely, what makes places like Proctor somewhat revolting—is that through these communities, visitors can envision a timeless era—a “golden age,” if you will—in which life was stable and simple. Healthy stands of trees encircle pastoral scenes of wooden homes and open meadows. The human-built world and the non-human-built world appear to coexist seamlessly. The empty farms are woven into the landscape. The Great Smoky Mountains usually gets credit for being the largest tract of wilderness in the eastern United States, but it also serves to commemorate America’s agrarian heritage. In an era of rapidly changing landscapes and increasingly interdependent communities, visitors want to believe that it is possible to live in a harmonious and stable relationship with the land.

Proctor, on the other hand, has no place in the agrarian frontier myth. There is something unsettling about it. Maybe it’s the overtly unharmonious relationship with nature that it represents. Maybe it’s the vision of industrial soldiers clearcutting 200-year-old forests that it evokes. Yet, Proctor would probably be the more appropriate way of commemorating the region’s frontier heritage. Communities like Proctor, built around extractive industries, became a common feature in the mountains even prior to the turn of the century. The mining and timber towns, not to mention the giant bonanza farms of the Great Plains, were the vanguard of capitalism, the reality behind the myth of the self-sufficient agrarian community. But we don’t like to see it that way, and so we sweep communities like Proctor under the proverbial rug. Perhaps it’s even comforting to see the overgrown ruins of Proctor in the forests of the southern Smokies and believe that such communities are remnants of a distant past. “I’m glad we don’t do that anymore,” is the likely refrain uttered by those hikers who pass by it. But we still do it that way, only the destruction is less overt and occurs primarily in developing countries.

Which brings me to the other most persistent myth in American environmental history: wilderness. The Smokies are hailed as the greatest stretch of wilderness in the eastern United States. But what exactly is wilderness? Americans, including me, want to believe that even in the most populated regions of the U.S. there remain areas of land outside the human realm, uncontrolled by human forces, in a state of wildness. It is an attractive idea and one that has driven environmental politics for a century, but, like all myths, it tends to obscure reality. In every wilderness setting, one can find the figurative human footprint. In some places like the Smokies, it might be entire towns swallowed up by the wild—or not. In others, it is a young forest of small trees, a silted waterway, the sound of chainsaws or snowmobiles. These remnants of human forces serve to demonstrate that wilderness as it exists today, especially in the eastern United States, is not a natural occurrence. Indeed, it is an idea that is culturally constructed and a reality that is politically, and then legally, enforced. The ultimate reason why Proctor and Cataloochee are abandoned is that they stood in the way of a national obsession to create wilderness.

As someone who loves these areas, this is part of the story that I have had difficulty embracing. But all wilderness enthusiasts must know it. Wilderness, in the form of national parks, was created by using eminent domain to force the purchase of lands from timber companies, individual smallholders, and in some cases Native Americans. (National forests were created with a little more empathy and involved purchasing land from mostly willing sellers). Wilderness creation saved habitats, protected species, and provided much-needed recreation to a growing urban population, but it was not a harmless process. In some cases, like Cataloochee and Cades Cove, people were displaced. They lost their homes, and that is truly regrettable.

Like William Cronon, I have come to accept that the wilderness myth may actually be doing harm to the future of environmental politics. This myth reinforces the belief that there exists a stark dichotomy between humans and nature. Wilderness is natural, whereas everything else is built by humans. It also might tend to aid reckless capitalist expansion by salving the conscience of environmental-minded people. If we pass enough laws and preserve enough land and species, we believe, then we can maintain a sustainable relationship with our environment without giving up any of our material well-being or limiting our population growth—in other words, without sacrificing anything. But we will be sacrificing. We will be sacrificing rural communities like Cataloochee, the inhabitants of which have historically made their living by harvesting the forest and converting natural resources into commodities. I have come to believe that in order to meet the global environmental challenges of the twenty-first century, we need to start with making local communities more sustainable. I also believe that environmental history can provide a lens and a language through which we can better understand the present environmental crisis.

The Palmer House at Cataloochee. Photo by Daniel Manget

Little Cataloochee Baptist Church. Photo by Daniel Manget.

The author in front of the sole remaining preserved building in Proctor, NC.