My Research

statement of research interests

My research explores the intersections of environmental history and social history in the American South. Specifically, I am interested in how ecology, markets, and communities created landscapes of subsistence in the southern countryside and how and why those landscapes changed over time. These landscapes, products of nature and culture, included both agricultural and non-agricultural ecosystems, a fact that many agriculture-oriented rural historians tend to overlook. Non-agricultural landscapes, such as streams, rivers, lakes, forests, and swamps provided valuable sources of food, medicine, recreation, and supplemental income. Questions of who could access these spaces and what resources they could use were answered partly by negotiations on a local level between landowners and commons users and partly by global currents of capital and national-level politics. Over time, rural communities developed a complex system of common rights under which unimproved, non-agricultural land remained something of a de facto commons where people harvested plants and animals for both their use value and their market value. Whether or not the fish, game, herbs, and other commons resources were used at home or traded as commodities, however, changed over time. Indeed, the social, political, cultural, economic, and ecological factors that created this complex web of use rights changed significantly over time, a fact that historians have not fully appreciated. The conservation movement that emerged around the turn of the twentieth century took aim at these common rights and attempted to impose another use regime onto the landscape in order to protect dwindling resources.

My research examines the social history of conservation and places it within a broader shift in political ecology that took place in the late nineteenth century. In short, the concept of political ecology involves the study of how political, cultural, economic, and ecological forces interacted at both the local and global levels to control who had access to what resources. Conservation historiography has long been dominated by a focus on federal conservation policy as it applied primarily to the western United States, including forestry, reclamation, and grazing. But as several recent historians have pointed out, the conservation impulse was present across the South as well, where it involved more of a widespread renegotiation of common rights on the local and state level. From this vantage point, we can see that movement was a more general attempt to replace the vernacular landscapes of subsistence with a more rationalized and orderly landscape, and it involved the grassroots as well as policy makers. We can also see that this movement included fence laws and ginseng laws in addition to game and fish laws. My research seeks to place the so-called conservation movement within the broader shift in political ecology and explore its implications for both rural communities and the nation as a whole.

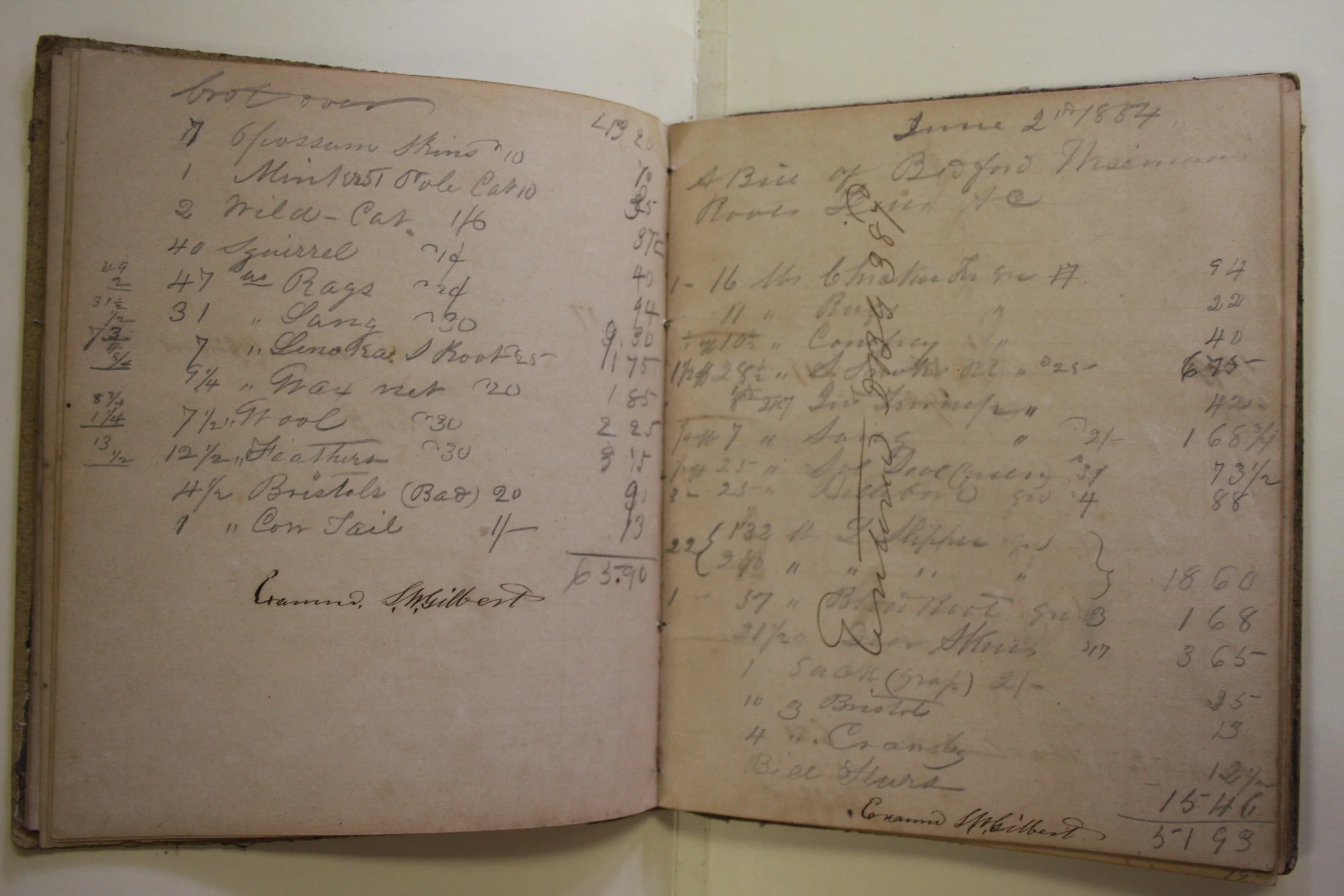

In my dissertation, “Sang Digger: An Environmental History of the Botanical Drug Industry in Southern Appalachia,” I argue that the Appalachian forest commons underwent significant changes over the course of the nineteenth century. During the antebellum era, the forests of Appalachia was utilized extensively by yeomen and landless farmers as a way to supplement farm production. Over the course of the late nineteenth century, animal furs and skins declined in commercial importance and, in some parts of Appalachia, roots and herbs became the dominant commons commodities. As markets for indigenous medicinal plants grew and expanded around the globe and the agricultural economy of the southern highlands struggled to recover from the Civil War, more people became more dependent on roots and herbs. In areas like northwestern North Carolina where the botanical drug trade reached unparalleled heights, people could find a wide variety of marketable roots and herbs on the forest commons, and many became specialists at harvesting them. This greater reliance on medicinal plants had significant impacts on the forest commons, as well as perceptions of Appalachian people. It led to the rapid depletion of some of the more lucrative plants like ginseng, or “sang,” as it was widely known. In communities like Pocahontas County, West Virginia, the disappearance of ginseng and the emergence of a class of people called “sang diggers,” who spent half the year searching for the root, generated tensions within communities. This led to a widespread renegotiations of common rights that took the form of state conservation laws aimed specifically at the sang diggers. In the 1870s, the name “sang digger” was used in local politics as a derogatory reference to someone opposed to progress, and over the next decade, a sang digger myth emerged in the pages of urban northern newspapers and magazines that painted the group as lawless, lazy, and degenerate. This myth served to reinforce the changing political ecology in the United States.

In addition to the botanical drug industry in Appalachia, my other research projects include a social history of fence laws in the South. From the 1870s through the 1910s, the political ecology of the grazing commons underwent a significant renegotiation. In the antebellum era, many livestock owners turned their stock out into the forests—regardless of who owned it—to forage on chestnuts, acorns, and other spontaneous productions of nature. However, by the late nineteenth century, southern communities took measures to curtail these rights and impose order on the landscape by passing a new round of fence laws that required livestock owners to fence in their stock. Because states like Georgia and North Carolina allowed local communities to vote on these measures, historians can access a plethora of sources that uncover the seams of conflict that divided communities over the fence question. Much of the scholarship on fence laws in the South are highly localized studies, and scholars generally disagree over what animated fence law proponents and opponents. In the future, I hope to add to the research I have conducted on Buncombe County, North Carolina, and write a comparative community study on the fence laws. Among other things, I hope to explore the role of race, ethnicity, and class in shaping the debate and the patterning of fence law adoptions across the South. Mart Stewart, Scott Giltner, and Louis Warren, among others, have significantly advanced the study of how African Americans and other ethnic minorities have constructed landscapes of subsistence and the racially uneven consequences of conservation laws. I hope to contribute to this growing scholarship by placing the fence law movement into the context of conservation.

My M.A. thesis addresses another aspect of this shift in political ecology in the South. It examines the campaign of rural reformers, such as Wilmington, North Carolina, businessman Hugh MacRae and University of North Carolina Professor of Rural Economics, Eugene C. Branson, to reconceptualize the relationship between rural communities and their environment. Part of the Progressive attempt to impose order on the countryside as a way to stifle what they saw as the deterioration of rural life, this group of men and women sought to redirect the modernization of Southern farms toward what I call the “community ideal,” a cooperative community model based on intensive cultivation of truck crops that aimed to preserve the small, independent yeoman farmer. This impulse created a few experimental communities and led to an influential but ultimately unsuccessful campaign to secure federal funding to create model communities. These progressives diverged from many of their contemporaries who believed that agriculture should adopt industrial methods of organization and production. However, these reformers, like other agricultural reformers, all but ignored the importance of non-agricultural landscapes of subsistence to the maintenance of rural communities. Indeed, they all wanted a rationalized and ordered landscape oriented toward efficient production. As a future project, I hope to write a more comprehensive study of how elite reformers, from country lifers of the Progressive era to the Regionalist school of the 1920s and 1930s, sought to reconfigure the rural landscape. I would also like to examine the history of utopian experimental communities from an environmental perspective, something that has not yet been done.

publications

* If you are interested in reading any of these, feel free to get in touch with me. I can send them along.

“The Panther in the American Mind: Wilderness Sublime and the Historical Roots of the Eastern Cougar Phenomenon,” American Studies (under consideration).

“Community and the Commons: Fence Laws, Land, and Identity in Postbellum Appalachia,” in Steven E. Nash and Bruce E. Stewart, eds., Southern Communities: Identity, Conflict, and Memory in the Nineteenth-Century American South (forthcoming, expected fall 2018, UGA Press).

“Ginseng, China, and the Transformation of the Ohio Valley, 1783-1840,” Ohio Valley History, Vol. 17, No. 3 (Fall 2017), 3-23.

“Nature’s Emporium: The Botanical Drug Trade and the Commons Tradition in Southern Appalachia,” Environmental History, Vol. 21, No. 4 (October 2016).

“Sanging in the Mountains: The Ginseng Economy in the Southern Appalachians, 1865-1900,” Appalachian Journal, Vol. 40, Nos. 1-2 (Fall 2012/Winter 2013).

“Backcountry Loyalty: How a Forged Letter Turned the Tide of the American Revolution in the South,” Tuckasegee Valley Historical Review, Vol. 23 (Spring 2012), 78-101.

Book Reviews

Feral Animals in the American South: An Evolutionary History, by Abraham Gibson, in Agricultural History, Vol. 92, No. 1 (Winter 2018).

Nature’s Civil War: Common Soldiers and the Environment in 1862 Virginia, by Kathryn Shively Meier, in Ohio Valley History, Spring 2015.

The Coal River Valley in the Civil War, by Michael B. Graham, in Civil War Monitor (published online April, 2015).

The Spirit of the Appalachian Trail: Community, Environment, and Belief on a Long-Distance Hiking Path, by Susan Power Bratton, in West Virginia History, Vol. 8, No. 2 (Fall 2014).